Exchange for Change

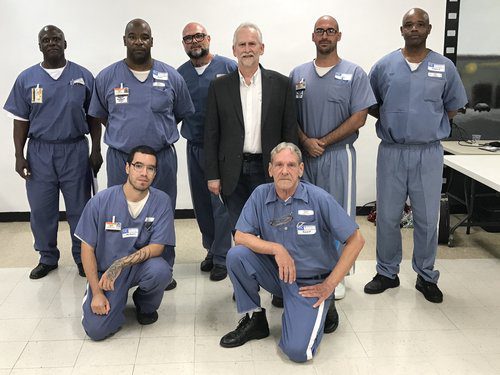

Exchange for Change is an innovative non-profit that provides high-quality, college-level writing courses to incarcerated students in the Florida corrections system.

Their teachers are experts in their fields, many of them college professors or longtime professionals, who are interested in sharing their knowledge with the incarcerated population. The organization reaches hundreds of students and currently offers over 25 courses across eight different institutions.

We sat down with founder and Executive Director Kathie Klarreich to learn more about how the organization began, and how it operates.

Describe for us Exchange For Change’s mission in your own words.

We’re a nonprofit organization that works in carceral settings, whether it’s prisons or jails or juvenile detention centers. The mission is really twofold: one is to provide communication skills, which we do through writing courses. And the second part of our mission is to bring the word of the incarcerated out to the public, because a vast majority of people who are incarcerated will be returning to our communities, and our communities have a misperception based on television and movies about who is in our jails and prisons. So, by allowing our students to use their own words, we bring their voices out and hope to dispel some of those preconceived ideas.

You’ve said that Bill Burdette, President and CEO of Impact Deposits Corp. was helpful in your founding of Exchange for Change. How did you two meet?

I’d been working with another nonprofit teaching in the women’s prison and we parted ways. So then I was sort of lost and I wanted to do something inside the prisons, but I didn’t know what, and my former colleague said, you oughta talk to this guy. I met with Bill and explained to him my vision to unite writers inside and outside of the Florida corrections system. He pulled out the yellow pad and said, “Ok, well, what are you gonna call your nonprofit?” He was incredibly instrumental because it was Impact Deposits Corp.’s support that allowed us to get up and running. Bill had some of his staff help us set up our website and bookkeeping. We maintained office space at the Center for Social Change, which also provided Exchange for Change with a lot of valuable contacts that we’ve kept in touch with, and it was our home for eight years.

I’ll tell you what Impact Deposits Corp. has helped us accomplish. This semester we have over 400 students with just a staff of two. We’re in eight institutions with some 20 instructors. And so much of this is volunteer work because we don’t have much money, but getting the quarterly donations from Impact Deposits Corp. covered just regular services, wifi access to people. Bill Burdette has introduced me to many people who’ve given us free counseling. But the money we receive, every penny is well spent because we’re super lean and the more money we get, the more courses we can offer.

Who teaches your courses?

Our instructors honestly are just an amazing group of people — either retired professionals, or currently teaching in academic settings, or they have some area of expertise. So, for example, we just started with a guy who’s 94 years old, who was an engineer for 70 years, worked on the Apollo, and is teaching a course for people who will be coming out of prison in less than three years. He’s at a reentry center and he is teaching students how to get a job in construction, along with writing.

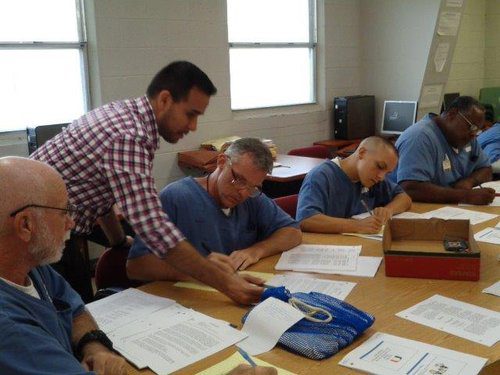

What happens in your classwork?

During classes we teach meditation and students keep a journal. We have a journalism course, so our people put together a newspaper. We teach traditional fiction, non-fiction and poetry, songwriting, screenwriting, a course called Trauma Toolbox that helps people figure out where their triggers are, and to divert those impulses into better communication rather than behavior that might have gotten them into prison to start with. The truth is that people who are incarcerated are a microcosm of society. So whatever interest you find outside in society, you have the same interests inside the prisons.

Exchange for Change pairs incarcerated students with university students for mutual correspondence. How does that work?

Let’s say you are a professor teaching a course on communication at the University of Miami; your students and my students will read the same thing, whether it’s a textbook or a writing prompt, or an essay. Then your students take on a pseudonym to protect their identity, and they write something and send it electronically to us. We print these papers out and bring them inside, so that our students can respond to yours. It becomes this semester-long communication between two people in two different settings that starts out on something technical or literary, and then just becomes a conversation between writers. And that fills both parts of our mission: the outside student often thinks that they’re going to be the mentor or the educator, but for the most part today’s students don’t write letters, they write texts. So the university students end up— I say this lovingly— being the ones who become better educated about their own biases and prejudices and stereotypes. It’s a chance for our inside students to improve their communication skills, feel like they’re connected, and that their opinion is valued and their voice gets to be heard.

How are your incarcerated students chosen for the program? Is it an open enrollment, or are there criteria?

The only course that the Florida Department of Corrections is required to teach is to allow incarcerated people to get their GED. So, when we were coming up with this program we started with general courses for anyone who has a GED. And what we’re finding now is that it’s very good preparation for people who want to go further and take advantage of a college education inside.

The other thing is that in the state of Florida, again, most programs are not available to people who have life sentences. And I would say about half of our students have life sentences. We feel education is a human right. Just because you’re locked up your access to education and to healthcare should still be provided. Ours is a volunteer program, anyone who wants to take our course can sign up and they’re in. We come in without an agenda other than to share our knowledge on writing. One thing incarcerated people are brilliant at is observation. You know, they spend all day studying people. And so I think we got buy-in from the beginning, from the right people. And that really helped our program grow

It seems one of the primary things that you give to prisoners is a voice.

Absolutely. We just started a project earlier this year where we’re bringing community members inside for a three-hour program. They take a tour of the prison, and then they sit down with up to 15 incarcerated people. And then they all break up into small groups, we give them guided prompts that most of them don’t follow! They just sort of take off. And at the end of the hour everyone comes back and sits around a table and offers reflections on what the afternoon was like. The impact of that program is very similar to the exchanges, but here our incarcerated students are actually sitting face to face with somebody who really wants to know about their life. We’ve had religious groups come in, meditation groups come in, just regular community folks. They all go back out and spread the word about what their experience was like. But then the guys on the compound, they go out and say, “Hey, we’re not forgotten. You know, people are coming in, they treat us like human beings. There’s hope for us when we go back out.”

Exchange for Change has published a book called Hear Us, which contains writings from the incarcerated people who are part of the program. Can you talk a little bit about that and how do I get a copy?

So, it’s on Amazon. This was a first for us. And it was a really incredible experience. Like the rest of the country, when COVID hit everything got shut down, including access to the prisons and to our students. And so we put out a call to all the prison programs we could think of across the country to reach their students and say, you know, can you write about this? Well, then obviously the pandemic didn’t last just two or three months, so we extended submissions to a later date and also asked incarcerated individuals to document their feelings about the murder of George Floyd. We ended up getting over 200 submissions for the book, which is called, Hear Us, Writing from the Inside During the time of COVID. It covers incarcerated individuals in 17 states representing a cross section of women in Alaska, to guys on death row in San Quentin, and a lot of our Florida students. It gave voice to people all across the country, many of whom were experiencing the same thing. We were concerned that everybody would be writing the same thing, but they didn’t. So we got funny short stories, we got gut wrenching personal essays, we got poems and haiku and drawings.

Is there a success story of an incarcerated student who has transitioned to the outside that you feel has really benefited from the program?

Can I answer that in another way, which is someone who has not gotten out and how it has changed his life. This is a guy who has tattoos everywhere, you know, on his eyelids, on his ear lobes, on his arms. And he came in, very quiet, sat in the corner, he didn’t say very much. And then when it was his turn to read, I thought, “My God, this guy is really a good writer!” That’s an understatement; he’s probably the most gifted writer I’ve ever met, who would have gone most likely undiscovered had we not had a platform for his voice to get out. We named him our first program Poet Laureate. He’s been in three or four anthologies. Two years ago, he was transferred to another institution in central Florida where he single handedly started the Exchange for Change program there, and now teaches four classes. And so he’s one of many, many, many people whose lives have changed as a result of having an opportunity to have a voice.